The first one-day Wood Bending Workshop occurred on Saturday, September 3, 2011, with two students in attendance. Marco Cecala is an accomplished woodworker and furniture maker interested in expanding his horizons, and David Keeling is a rehabilitated airline pilot who wants to make wooden surfboards using bending techniques. The day was devoted to exploring the different ways that wood can be bent: steam treatment, hot pipe bending and bent lamination.

Air dried wood, at about 15%MC, is the preferred material for both steam and hot pipe bending, because the lignin has not been dried out excessively in the kiln and still plasticizes easily in the presence of heat. Since we are not blessed with a reliable source of air dried hardwoods in Arizona, it’s good to know that kiln-dried wood will also bend — though not so easily, and with a higher expected failure rate and a more unpredictable spring-back factor.

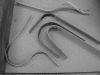

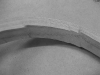

Bending kiln-dried wood is only possible with the use of a compression strap — a stiff but flexible steel strap with stop blocks bolted in place that precisely capture the length of the stick to be bent. The strap forces nearly the full thickness of the stick into compression, allowing only a bit of tension stress on the convex side of the bend. Wood stretches under tension only a small amount before failing (i.e., breaking rather dramatically), while it can be compressed very substantially before buckling. We bent 42″ (107cm) long sticks, 3/4″ x 1-1/4″ (19mm x 32mm) in cross section, into a ‘U’ shape around a 6-1/2″ (165mm) radius form. The most agreeable sticks made the trip with no discernible tension or compression stress whatsoever. Measured after cooling, the outside (convex) face of the stick was still 42″ (107cm), while the inside (concave) face of the stick averaged 39-3/4″ (101cm), a difference of 2-1/4″ (57mm)!

In the workshop we made these 42″ (107cm) bends using kiln-dried ash, hickory, walnut, cherry, maple and alder. We saw minor tension and compression stress evidence in some pieces of virtually all the species used, but several pieces bent perfectly. Ash is a predictable performer, as is hickory, and the oaks are fairly reliable. Our favorite on the day was the walnut (easiest to bend, least stress evidence, no failures). A couple of pieces of cherry also fared very well. When choosing pieces to be steamed and bent, use only the straightest grain stock you can find.

The ‘hot pipe’ is an effective method of heating thinner strips of wood for bending. It has been used for a long time by musical instrument makers to form the sides of violins, guitars and similar instruments. It can also be used in furniture making and wood craft work for making things such as chair back slats and wooden utensils. The wood is typically soaked in water for several hours prior to heating. Air dried stock up to about 3/8″ (10mm) thickness can be successfully bent on the hot pipe, kiln dried stock up to about 3/16″ (5mm). The section of the soaked piece to be bent is warmed on the surface of the pipe until it is felt to ‘relax’, or soften. Keeping the piece warm and working it on the pipe, it can be coaxed into fair curves and even very radical bends. A little scorching is typical, but can be scraped or sanded away after cooling and drying.

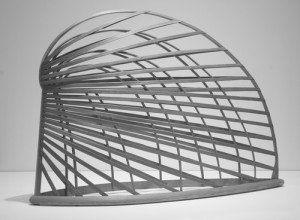

Bent (cold) lamination is arguably the most direct and effective way for most woodworkers to bend wood. The material is sawn into thin sections – typically 1/8″ (3mm), more or less – that are individually pliable enough to be bent cold to the intended form. Stacked up with glue between each layer, the stack is progressively clamped firmly to the form and remains clamped until the glue has thoroughly set. Preferred glues for bent lamination are the urea formaldehyde types because they cure hard, are not thermoplastic, and do not ‘creep’ (i.e., allow the laminates to ‘slip’ in reaction to the laminates’ tendency to try to spring back to an unbent condition).

Please peruse the following gallery of images from the workshop to get an idea what we were doing. If you’re interested in learning more about bending wood, considering signing up for my workshop the next time it comes on the schedule.