(* – apologies to the late Johnny Burnette … df)

My introduction to steam-bending wood was in the mid-1970’s in northwest Alaska. We got into building dog sleds and boats, and making and repairing snowshoes. The Inuit people had always used green birch, harvested regionally, for bending parts for such things. In the ’70’s it was more common to use hickory that was barged in every summer (the nearest road was 300 miles east). These kiln-dried 50mm planks came from who-knows-where, and if at the time we had known or cared about moisture content we probably would have thought twice about trying to use it for bending.

But we forged ahead, learning the local bending customs from the old-timers. There was little agreement on processes — everyone had their own favorite secrets, divulged grudgingly — and the failure rate was significant, even for mild bends like dogsled runners. No one really knew about or understood the science involved, practical place as it was you just had a go at it using what you thought you knew or had learned from previous experience.

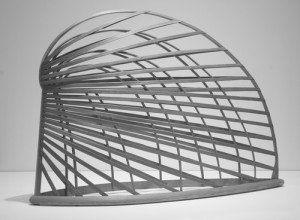

Martin Puryear. Bower. 1980. Sitka spruce and pine, 64" x 7' 10 3/4" x 26 5/8" (162.6 x 240.7 x 67.6 cm). Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington D.C. Museum purchase made possible through the Luisita L. and Franz H. Denghausen Endowment, Alexander Calder, Frank Wilbert Stokes, and the Ford Motor Company. Photograph by Richard Barnes. © 2007 Martin Puryear

My first bending epiphany was provided by brothers Michael and Martin Puryear, who in 1980 or so kayaked the Noatak River and ended up camped on the coast next to us near Kotzebue. We were building a boat, and in the process of bending the chines. The Puryears were both woodworkers — Michael today is a well-known furniture maker in upstate New York, and Martin is a famous sculptor and wood artist — and both were experienced and educated in the process of bending wood. I’m sure they thought our uninformed, backyard efforts were nuts, but they gave us some great advice and later, after they were home in New York, sent me some excerpts from the USDA Forest Products Lab’s pub. #215, Bending Solid Wood.

In the 1980’s and ’90’s I came to rely on bending information written by Bill Keyser and Michael Fortune published in Fine Woodworking Magazine’s compilation Fine Woodworking on Bending Wood. (the book is still available from Amazon) In more recent years I have had the opportunity to see Fortune’s wood bending demonstrations at conferences and other venues, and became convinced — the eyes don’t lie — that he had the whole thing pretty well figured out. Michael has been my wood bending ‘guru’ ever since.

There is a lot of literature out there on bending wood with steam, and if you read through it it’s not hard to avoid the comparison with my Inuit friends from long ago — not everyone agrees on every aspect of the process. But there are a few constants that I think can be set down as rules:

- Air dried wood (avg. 15%mc) is ideal for steam bending. In air dried stuff the lignin and cell walls have not been ‘cooked’, as in kiln drying, and can still be easily plasticized by heat. Kiln dried wood responds to steam and can be bent, but especially in thicker sections the results are much less predictable and satisfactory than using air dried material.

- Use straight-grained, defect-free stock. If your piece has significant runout, inclusions or pin knots, or almost any defect at all — you’re asking for trouble.

- Steam wood one hour per inch of thickness. If your steam box is cranking (lots of very hot steam blasting out of every nook and cranny), that’s all it takes whether heating air or kiln dried wood.

- Use a steel compression strap whenever possible. If bending air dried wood, you may be able to skip this for milder bends, but it’s essential for radical bends. And if bending kiln dried wood, a steel compression strap is required for all bends, radical or mild — if you want to have any hope of avoiding failure.

- No rules are absolute! Sometimes things seem to work OK in spite of all evidence to the contrary. But following the rules above will generally give you the best chances for consistent success.

There are other ways of bending wood — the hot pipe for example, which has been used for a long time (centuries?) for bending violin sides, and can be used on air-dried stock up to about 10mm thickness (and on kiln-dried stock up to maybe 4mm. Bent lamination is the other chief bending method, in which thin layers of wood are glued and clamped to a shaped form.

Adding bent wood to your repertoire of woodworking techniques greatly expands your horizons as a woodworker and furniture maker. If you are interested in the process and a chance to try it in a hands-on environment, consider signing up for my one-day bending class (offered periodically). The workshop provides an introduction to steam bending, hot pipe bending and bent lamination.

Please see the following post for a description of the first bending class, held Sep. 3, 2011, including an image gallery from the class.

One Response to “Steamin’, I’m always steamin’ …”*